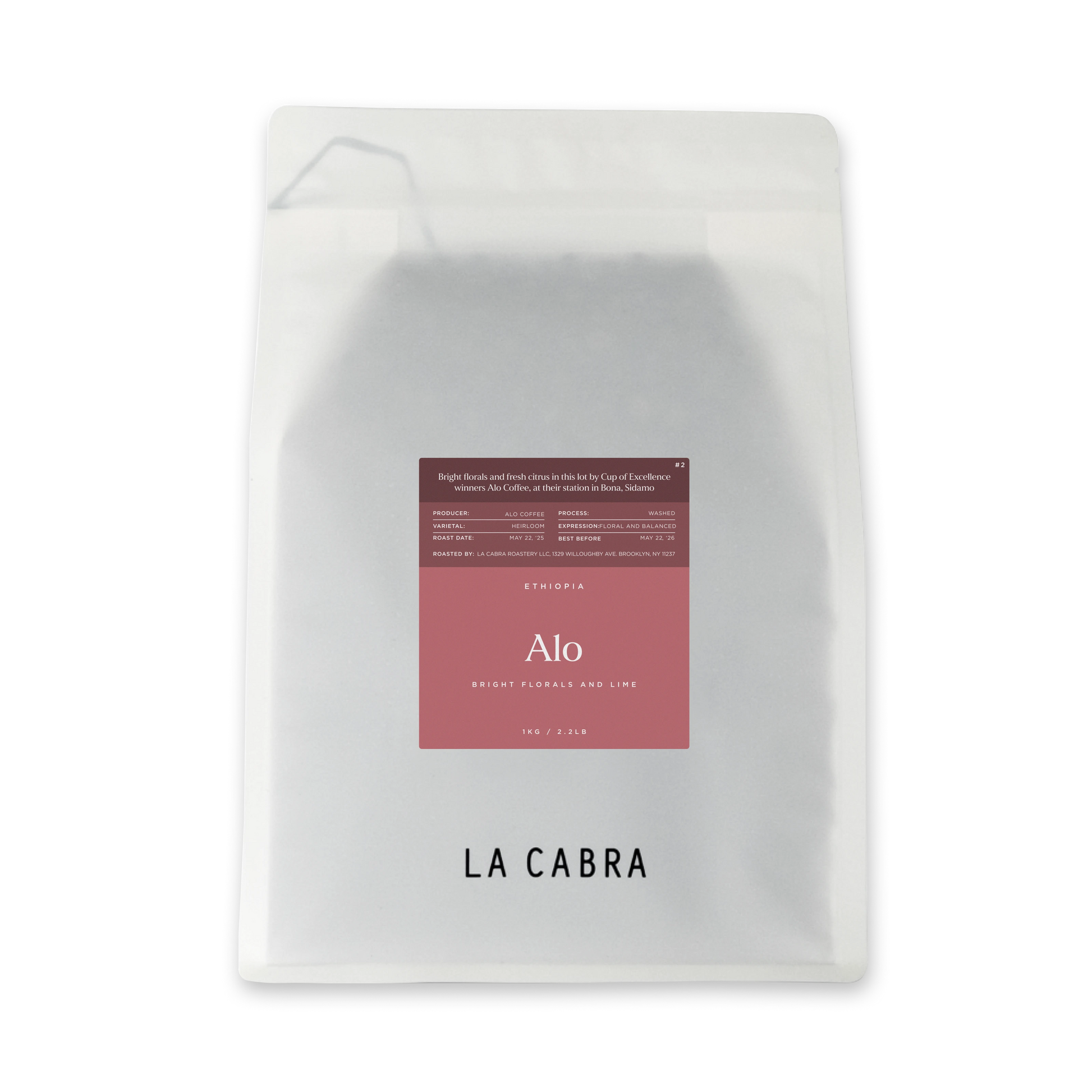

Tamiru Tadesse

Tamiru Tadesse was previously an electrical engineer and a university lecturer. Tamiru began working with coffee part time, but became frustrated with constantly unfair pricing and undervalued labour. Tamiru’s dream was to bring more value home to Ethiopia, helping the coffee industry to understand the incredible work being done here. For many years, Tamiru watched on from the sidelines, reluctant to launch something of his own until Ethiopian coffee could be valued in the same way as coffee from Colombia or Panama.

-v1761587292074.jpg?878x752)

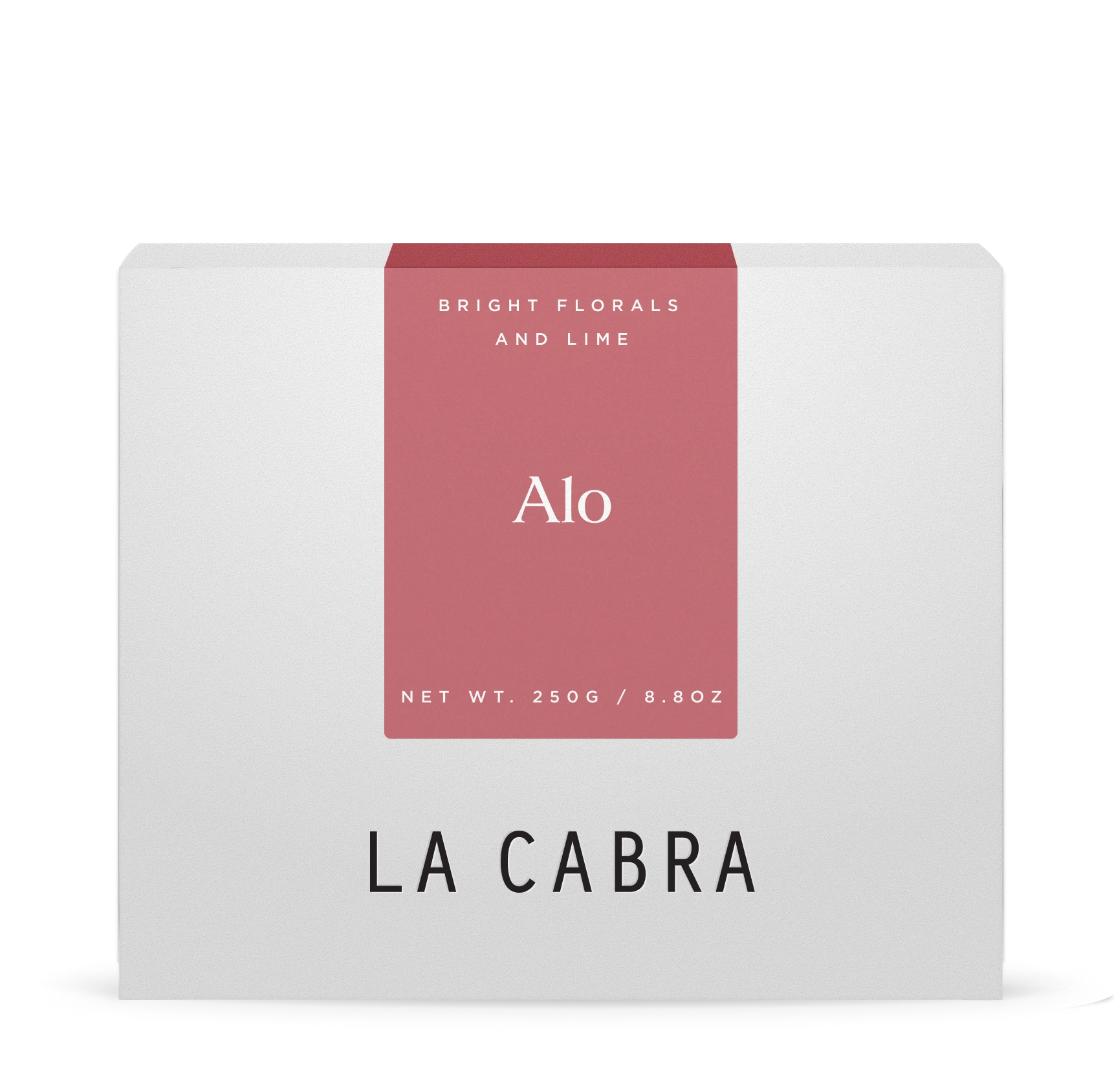

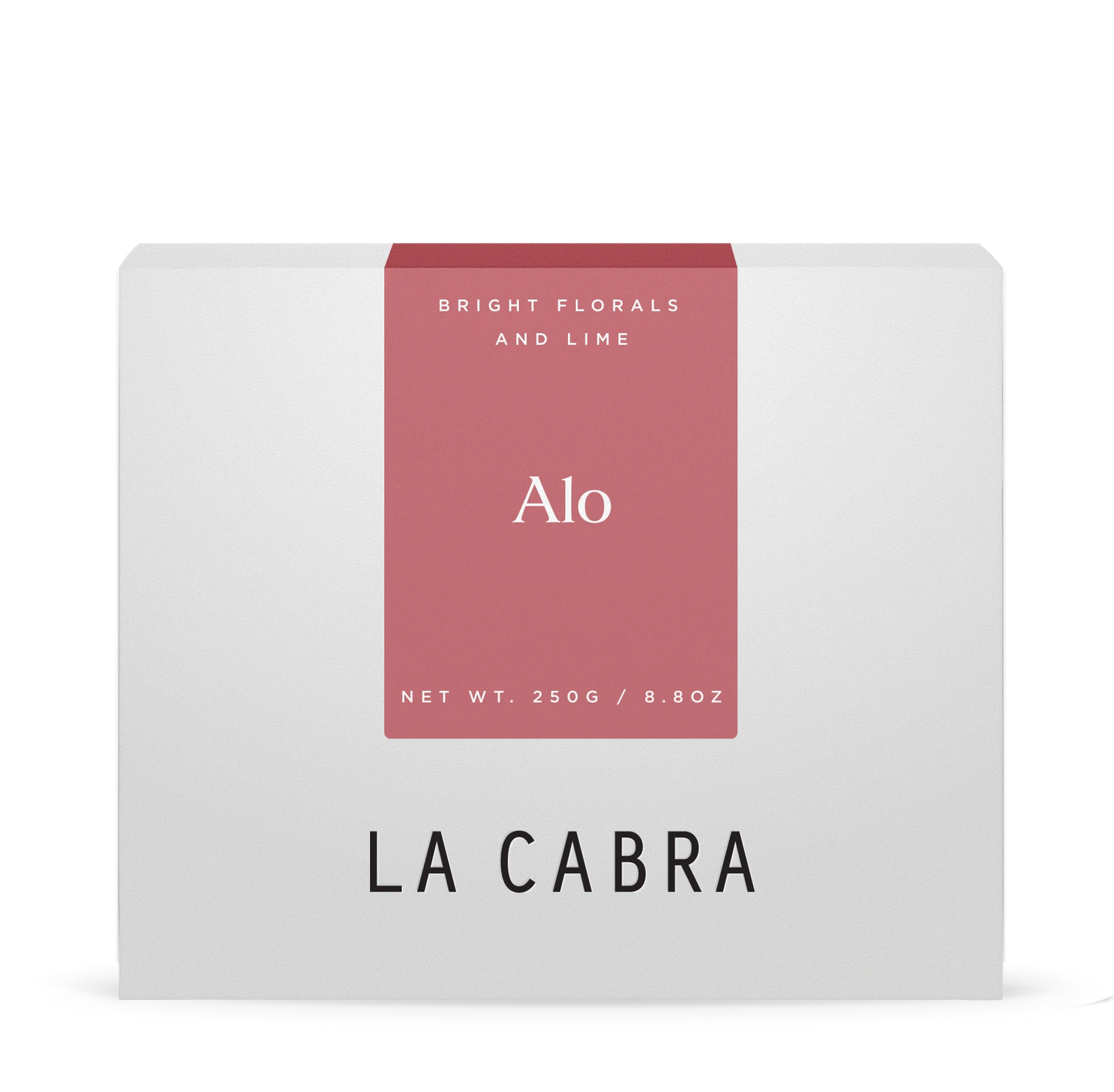

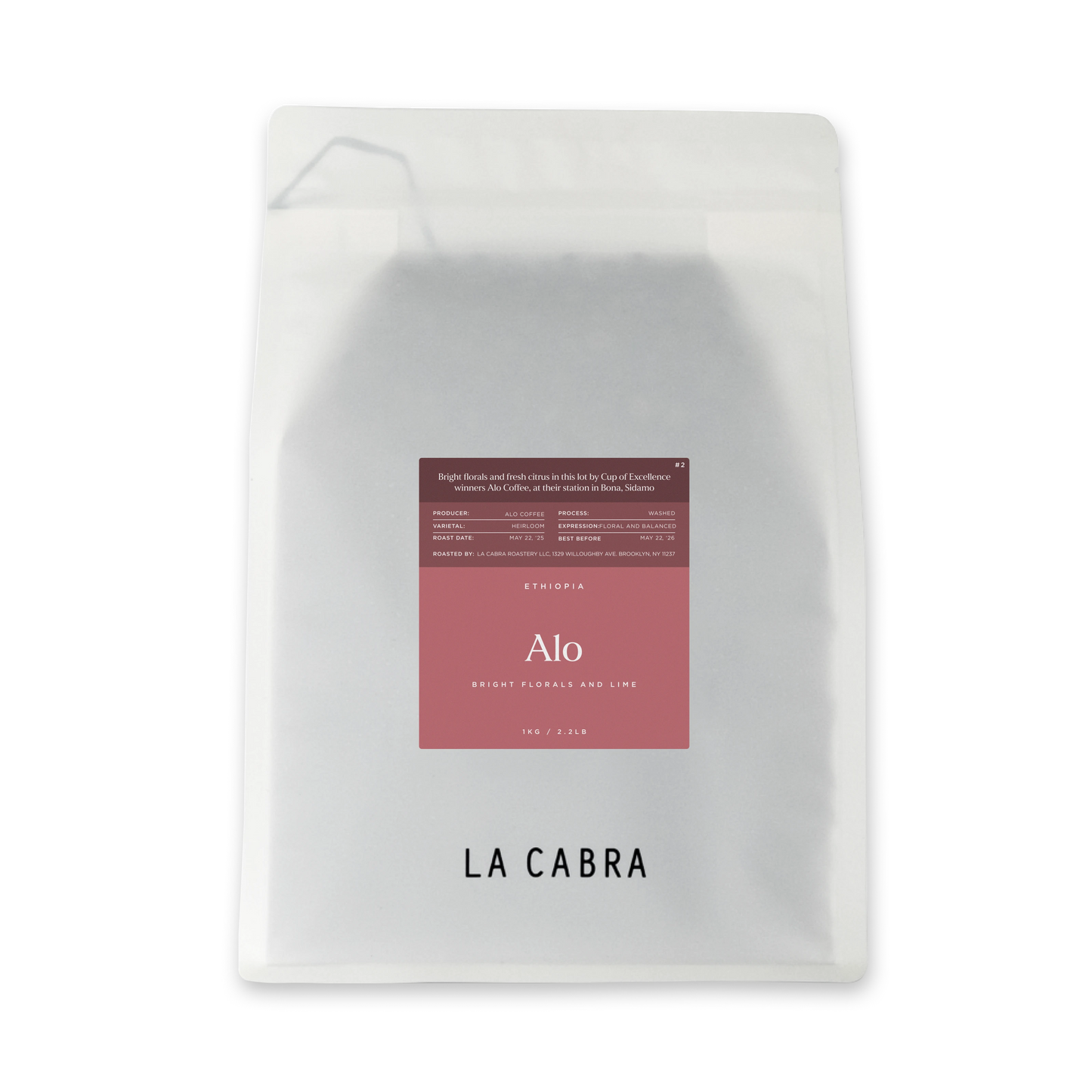

Alo Coffee

The years following the changes in Ethiopian Commodity regulation in 2017 were chaotic and fast moving, creating a market for greater traceability and quality in Ethiopia. In 2020, Ethiopia held its first-ever Cup of Excellence, a revelation that proved exceptional Ethiopian coffees could be found, celebrated and rewarded. This was the signal, together with his wife, Messi, Tamiru set out to prove that Sidama’s finest coffees could stand among the world’s best. In 2021, their first submission to the Cup of Excellence, a lot from their home village of Alo in Bensa, won the competition outright, changing their lives forever.

-v1761587292632.jpg?1200x800)

Bona Zuria

In the intervening years, Tamiru has been able to travel the world searching for inspiration, continuing his pursuit of the finest quality coffees. We first met in Panama, touring the iconic Elida and Esmeralda estates together, and have stayed in contact since. We met Tamiru at the Alo office for the first time earlier this year, cupping through tables of coffees from across the Alo stations in Sidamo. This lot is from their station in the Bona zone, just outside the village of Zuria. The washed process leads to a crisp and clean expression of the Sidama terroir, with bright floral aromas followed up by fresh lime and a soft black tea tea finish.

-v1761587293273.jpg?1200x800)

Ethiopia

In Ethiopia, coffee still grows semi-wild, and in some cases completely wild. Apart from some regions of neighbouring South Sudan, Ethiopia is the only country in which coffee is found growing in this way, due to its status as the genetic birthplace of arabica coffee. This means in many regions, small producers still harvest cherries from wild coffee trees growing in high altitude humid forests, especially around Ethiopia’s famous Great Rift Valley.

-v1761587293855.jpg?900x1350)

Forest coffee makes up a great deal of Ethiopia’s yearly output, so this is a hugely important method of production, and part of what makes Ethiopian coffee so unique. Deforestation is threatening many of coffee’s iconic homes in Ethiopia, leading to dwindling yields and loss of biodiversity; significant price fluctuations over the past decade have led many farmers to replace coffee with fast growing eucalyptus, an incredibly demanding crop in terms of both water and nutrient usage.

-v1761587294401.jpg?900x1124)

Throughout these endemic systems, a much higher level of biodiversity is maintained than in modern coffee production in much of the rest of the world. This is partly due to the forest system, and partly down to the genetic diversity of the coffee plants themselves. There are thousands of ‘heirloom’ varieties growing in Ethiopia; all descended from wild cross pollination between species derived from the original Arabica trees. This biodiversity leads to hardier coffee plants, which don’t need to be artificially fertilised.

This means that 95% of coffee production in Ethiopia is organic, although most small farmers and mills can’t afford to pay for certification, so can’t label their coffee as such. The absence of monoculture in the Ethiopian coffee lands also means plants are much less susceptible to the decimating effects of diseases such as leaf rust that have ripped through other producing countries. Maintaining these systems is important, both within the context of the coffee industry, and for wider biodiversity and sustainability.