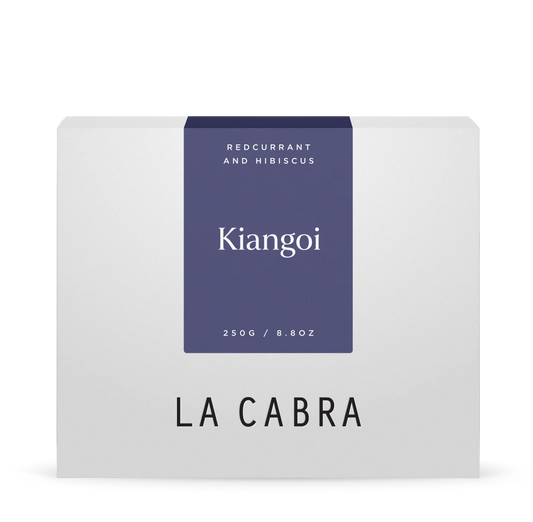

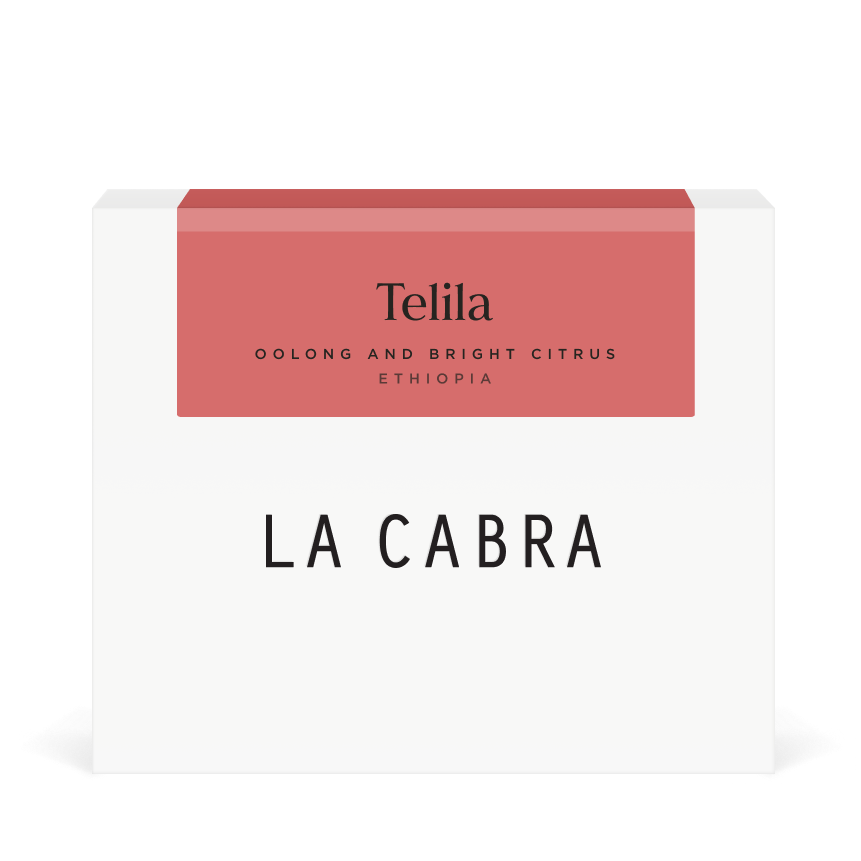

Mike Mamo has only been running the Telila washing station since 2019, encouraged by the liberalisation of the Ethiopian coffee industry in 2017. The opening of regulations allowed much smaller lots to be exported, and more traceability to be maintained, allowing the building of relationships down to the farm level. Mike, an Ethiopian American born and raised in Addis, has recently taken over the milling and exporting company his father started 65 years ago. Mike’s lifetime of experience in the industry meant that he saw the opportunity to create greater value for roasters and producers alike.

-v1722991882848.jpg?3712x4641)

The Telila mill, located in the Jimma region, processes coffees separated into day lots from small villages surrounding the mill, aiding in traceability and quality control. They also work with several larger farms, who produce enough coffee to export as a single lot. We have tasted several delicious coffees from the Telila mill, but this lot comprised of cherries from the village of Gure Kesso, was a highlight for us. Crisp florals and a delicate oolong tea character are highlighted by crisp citrus, a perfect illustration of the character of washed Ethiopian lots.

-v1722991889186.jpg?3247x4059)

In Ethiopia, coffee still grows semi-wild, and in some cases completely wild. Apart from some regions of neighbouring South Sudan, Ethiopia is the only country in which coffee is found growing in this way, due to its status as the genetic birthplace of arabica coffee. This means in many regions, small producers still harvest cherries from wild coffee trees growing in high altitude humid forests, especially around Ethiopia’s famous Great Rift Valley.

-v1722991885765.jpg?4674x3739)

Forest coffee makes up a great deal of Ethiopia’s yearly output, so this is a hugely important method of production, and part of what makes Ethiopian coffee so unique. Deforestation is threatening many of coffee’s iconic homes in Ethiopia, leading to dwindling yields and loss of biodiversity; significant price fluctuations over the past decade have led many farmers to replace coffee with fast growing eucalyptus, an incredibly demanding crop in terms of both water and nutrient usage.

-v1722991891215.jpg?3854x4817)

Throughout these endemic systems, a much higher level of biodiversity is maintained than in modern coffee production in much of the rest of the world. This is partly due to the forest system, and partly down to the genetic diversity of the coffee plants themselves. There are thousands of ‘heirloom’ varieties growing in Ethiopia; all descended from wild cross pollination between species derived from the original Arabica trees. This biodiversity leads to hardier coffee plants, which don’t need to be artificially fertilised. This means that 95% of coffee production in Ethiopia is organic, although most small farmers and mills can’t afford to pay for certification, so can’t label their coffee as such. The absence of monoculture in the Ethiopian coffee lands also means plants are much less susceptible to the decimating effects of diseases such as leaf rust that have ripped through other producing countries.

-v1722991893494.jpg?4901x6126)

Maintaining these systems is important, both within the context of the coffee industry, and for wider biodiversity and sustainability. Our primary partners in Ethiopia, Moplaco, have made it their mission to inform of this destruction, and to continue supporting the communities they work with in order to make coffee a profitable and attractive business for smallholder farmers.

-v1722991896158.jpg?3593x4491)