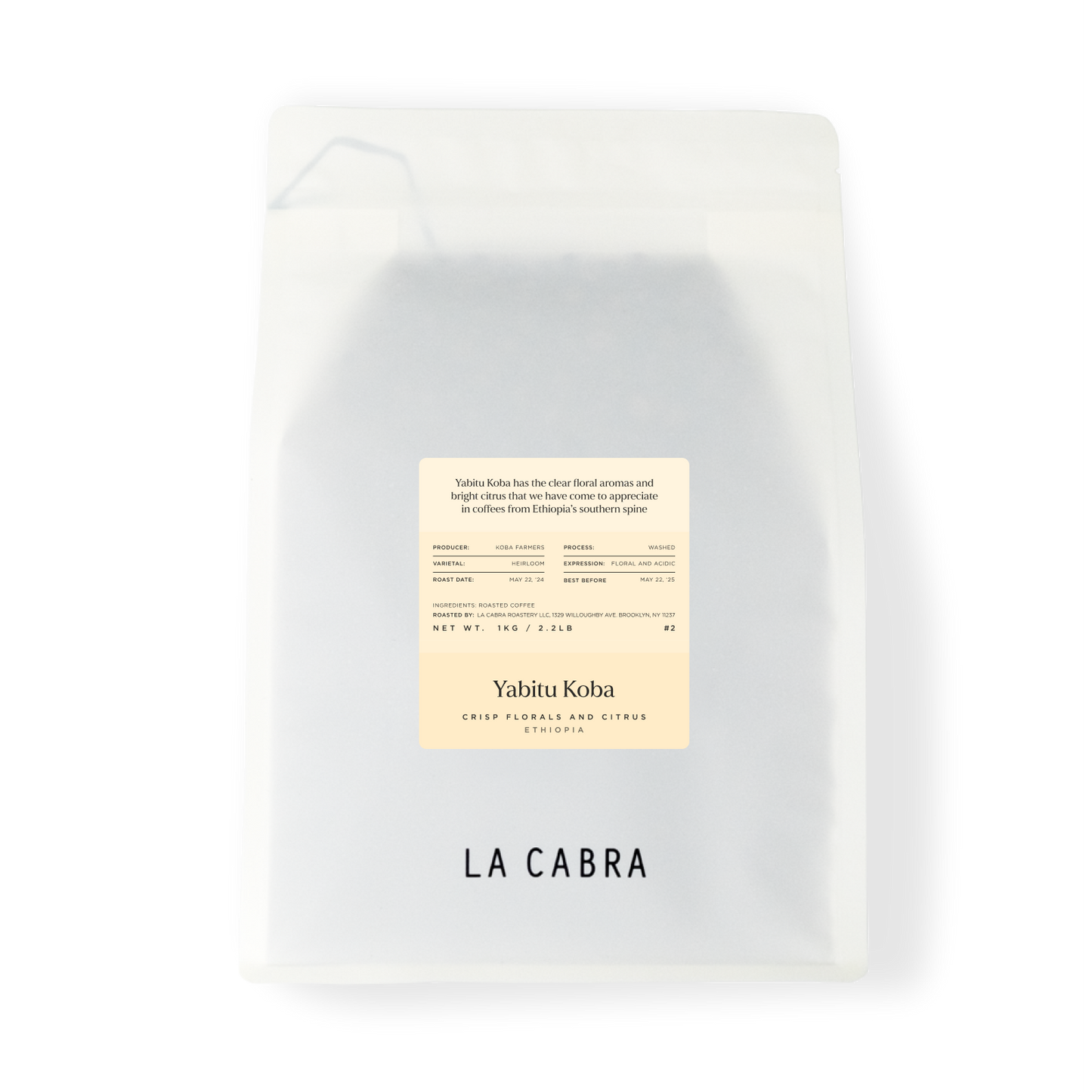

Yabitu Koba

This lot is composed of cherries collected from the village of Koba in Guji, and processed at Welichu Wachu’s station just outside of town. Guji lies in the southern Ethiopian highlands, in the same Rift Valley as the Yirgacheffe and Sidamo coffee growing regions. Koba is one of Guji’s many small coffee growing villages, lying in the Uraga sub-region at an altitude of over 2300 masl. Even by Ethiopian standards, this is a rural area, with many producers transporting their ripe cherries across long distances by donkey or mule, using dirt roads to reach the washing station.

Farmers here intercrop their coffee with both food crops and shade trees, especially with false banana, used throughout the coffee regions of Ethiopia. ‘Koba’ is in fact Oromiffa for false banana, such is the importance of the crop here. The plant’s symbiotic relationship with coffee trees, and the porridge-like dish that can be made from its starchy fruit, lead to its popularity across rural Ethiopia. The quiet rural lifestyle is striking here. Many have only ever worked with coffee, together with and at the mercy of nature. This close relationship and observation, alongside favourable conditions and soil, leads to excellent quality, without the use of external inputs such as pesticides and fertilizers.

This lot is processed by Welichu Wachu’s team using a careful washed process. The very high altitude means very cool conditions, especially overnight, leading to long fermentations, sometimes as long as 60 hours. This leads to a complex flavour profile, here showcasing the clear floral aromas and bright citrus we have come to appreciate in coffees from Ethiopia’s southern spine.

Ethiopia

In Ethiopia, coffee still grows semi-wild, and in some cases completely wild. Apart from some regions of neighbouring South Sudan, Ethiopia is the only country in which coffee is found growing in this way, due to its status as the genetic birthplace of arabica coffee. This means in many regions, small producers still harvest cherries from wild coffee trees growing in high altitude humid forests, especially around Ethiopia’s famous Great Rift Valley.

Forest coffee makes up a great deal of Ethiopia’s yearly output, so this is a hugely important method of production, and part of what makes Ethiopian coffee so unique. Deforestation is threatening many of coffee’s iconic homes in Ethiopia, leading to dwindling yields and loss of biodiversity; significant price fluctuations over the past decade have led many farmers to replace coffee with fast growing eucalyptus, an incredibly demanding crop in terms of both water and nutrient usage.

-v1728049394424.jpg?1440x1440)

Throughout these endemic systems, a much higher level of biodiversity is maintained than in modern coffee production in much of the rest of the world. This is partly due to the forest system, and partly down to the genetic diversity of the coffee plants themselves. There are thousands of ‘heirloom’ varieties growing in Ethiopia; all descended from wild cross pollination between species derived from the original Arabica trees. This biodiversity leads to hardier coffee plants, which don’t need to be artificially fertilised. This means that 95% of coffee production in Ethiopia is organic, although most small farmers and mills can’t afford to pay for certification, so can’t label their coffee as such.

The absence of monoculture in the Ethiopian coffee lands also means plants are much less susceptible to the decimating effects of diseases such as leaf rust that have ripped through other producing countries. Maintaining these systems is important, both within the context of the coffee industry, and for wider biodiversity and sustainability. Our primary partners in Ethiopia, Moplaco, have made it their mission to inform of this destruction, and to continue supporting the communities they work with in order to make coffee a profitable and attractive business for smallholder farmers.